Each year, we dump 2.12 billion tonnes of waste into landfill. What if we could take that down to zero?

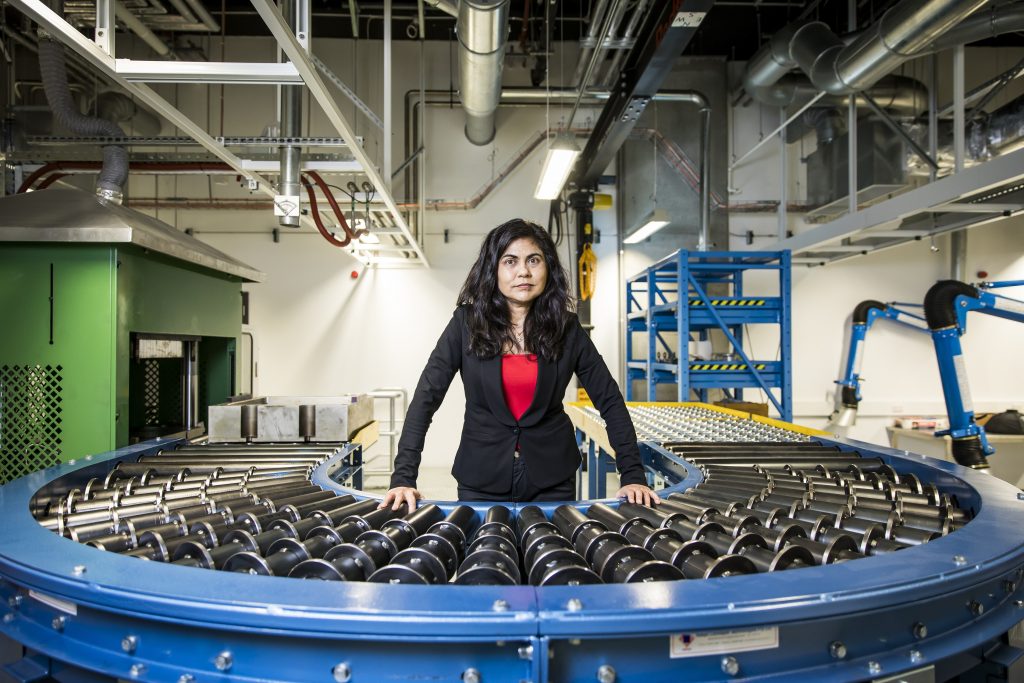

That’s the goal of Professor Veena Sahajwalla, who has been revolutionising the science of microrecycling by using waste as a resource for manufacturing. The inventor of ‘green steel’ technology and the world’s first e-waste micro-factorie, she is reimagining how we create and how we recycle.

Making things has always been a passion of Sahajwalla’s. And her roots—walking through the streets and factories of Mumbai as a child—remain central to everything she does. From those wanderings, she learned that everything could be repaired and given new life. And, just as importantly, that this work could create livelihoods.

Mumbai is such a fabulous city, with so much going on,” Sahajwalla told The Brilliant. “As a child, it was about understanding, first and foremost, how people actually make a living. It always impressed me how people would make a living by fixing shoes or clothes, or fixing all kinds of electronic stuff that we had at home. To me, it was really fascinating, because it was this creation of all these products out of things that were supposedly broken.”

Sahajwalla moved to the USA to do her PhD at The University of Michigan in Materials Science and Engineering . “What shocked me was that everything was so neat and proper,” she recalls. “I think in a strange way it bothered me.”

Sahajwalla moved to Sydney, Australia, where she became the founder and director of the Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) at UNSW Sydney in 2008.

As part of her work at the centre, she invented green steel manufacturing technology – an environmentally friendly process that injects recycled rubber tyres in electric arc furnace (EAF) steel making. Now used in factories around the world, this technology has prevented millions of junk tyres from ending up in landfill. The process releases some greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, says Sahajwalla, but its carbon footprint is smaller than that of conventional steel plants.

Australian steel maker Molycop has licenced the technology, and continues to work with Sahajwalla on other waste products that could be used, including coffee grounds to replace coal. The ambition is to completely remove coal from EAF steel manufacturing.

Small but mighty

Those early observations from the markets of Mumbai continue to influence Sahajwalla’s work. In 2018, she launched her e-waste ‘microfactorie’ and in 2019 her demonstration microfactories for green ceramics and plastics, respectively reforming waste glass and textiles, and waste plastics, into new products. Microfactories can be installed in an area as small as 50-100 square metres. Located near waste stockpiles and tailored to the needs of the local community, these tiny factories could be a boon for remote and regional communities.

Imagine that instead of throwing away your old glass and textiles, you have a local microfactorie, where you could bring them in and drop them off for recycling,” says Sahajwalla. “And voilà, when you walk to the other end, you may decide to buy green ceramic tiles that have been created from those old broken bits of glass and textiles.”

Sahajwalla envisions these microfactories as each having a different capability, but working in a collaborative eco-system. “If you’ve got four or five towns in a region, that collaboration means four or five different microfactorie modules,” she says. “You go to them just like you go to different shops and you buy different things. Their different capabilities give every operator the ability to specialize in making different kinds of products.”

Since 2019, Sahajwalla and her team at UNSW have launched a micro-factorie with local industry and government partners. Based in Cootamundra, a town in the South West Slopes region of New South Wales, recycles glass and textiles into ‘green’ ceramics.

“With the green ceramics micro-factory, we literally went from a demonstration unit at UNSW to commissioning the micro-factory at Cootamundra in a two-year period,” she says.

While glass is recyclable into more glass, in a conventional process, Sahajwalla’s microfactorie does recycling and remanufacturing, demonstrating that this world’s first technology can address environmental and social challenges with cost-effective micro solutions.

Beyond traditional manufacturing

The opportunities for microfactories extend well beyond traditional manufacturers, and they are accessible, says Sahajwalla – a science or technology background is not needed to operate them.

“Our partner for the Green Ceramics microfactorie was somebody who was already collecting mattresses to recycle. That’s a good example where you say, ‘There are a lot of good reasons why he should be the manufacturer for green ceramics,” she says.

Sahajwalla says the microfactories that are already in operation are awakening new ideas in other potential partners and exciting local communities.

“You only make what you need, you consume what you need, and I think that’s really the essence of what a microfactorie is all about,” she says. “You don’t over-consume, and at the local level, you can take care of your community.”

With her microfactories and green steel technology, Sahajwalla is creating a new era in manufacturing, where products are created from primarily waste materials, and landfill might become a thing of the past.

Quite often, as human beings, we get busy, and it’s overwhelming, and you often do wonder, ‘What can I do as an individual?’” she says. “There is a lot we can all do. What’s embedded in me from growing up in Mumbai is there is so much about modern-day habits of consumption that we can rethink.”

Article by Kylie Ahern

Photo Credit: Anna Kucera