The Tibees YouTube channel, started as a hobby, originally featured kittens and squeaking baby sloths.

“I remember getting a hundred subscribers,” founder Toby Hendy tells The Brilliant. “It was a really big moment for me.”

Today there isn’t a sloth to be seen, although there is the occasional cat. Tibees is now a physics and mathematics channel with more than 610,000 subscribers and 65 million total views. And it’s a full-time occupation.

Small beginnings

Hendy uploaded her first video in 2011 at age 15, the year she was selected by the Royal Society of New Zealand to attend the USA International Space Camp.

She made videos while studying physics at the University of Canterbury, just for fun, and kept it up during her studies at the ANU in Canberra. “I started making content about being a PhD student. Those really found an audience.” Deciding to take YouTube more seriously, Hendy created an upload calendar.

The growth of her channel was so explosive that Hendy left her PhD studies. Today she is a full-time science communicator, earning advertising revenue and Patreon donations. Key to her success is her creative yet calm delivery, which makes even the most complex mathematics seem accessible.

Her content stream The Joy of Mathematics, for example, is done in the style of Bob Ross, the American host of a popular TV show from the 1980s and 90s called The Joy of Painting. Following Ross’ lead, Hendy takes a chalkboard easel into nature and talks the viewer through calculus, or logarithms, while sketching mountains or trees.

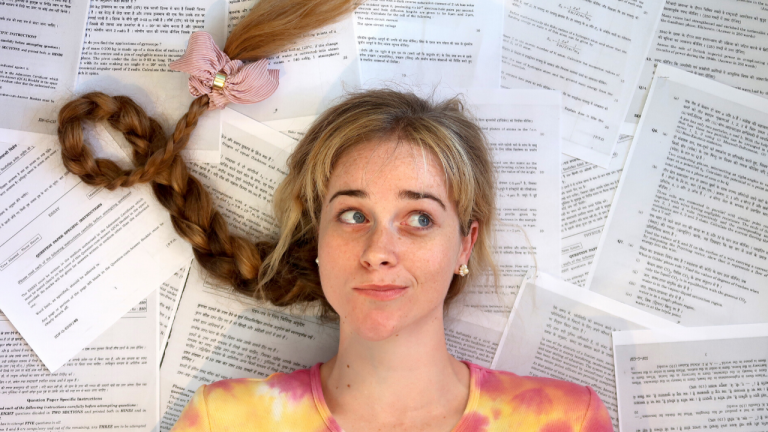

Another popular stream is Unboxing Exams, where she dives into an exam paper, like this astrophysics test from MIT in the USA. “The audience for those types of videos is fastest growing by far in India,” she says, because Indian students want to know how their exams stack up against their international equivalents.

Hendy gets people writing and telling her that her “channel has helped inspire them either to go back to school, or to want to pursue science or maths”. She thinks it may be the effect of hearing someone talk about maths as if it’s an everyday subject, rather than something to be frightened of.

When I was growing up, I lived in a small country town in New Zealand. I didn’t really know many people who had been to university –I don’t think I ever would have become interested in science if it wasn’t for the YouTubers who were doing it back in the early days,” says Hendy.

The secrets of YouTube

It’s widely believed that the algorithms control everything that people watch, through promoting some videos over others. Hendy, however, thinks they simply understand what people want to watch. “You need to cater to what will appeal to people,” she says. “Then you and the algorithm will work together.

Hendy says the most important part of any video is the title and thumbnail – the quick snapshot that viewers see when browsing YouTube. “You should actually plan the title and thumbnail before you even plan and film a video.”

Hendy then spends a minimum of two days planning and researching her topic, and then another day filming.

I try to upload once a week, or at most, every fortnight.” Hendy taught herself to edit and, despite her growing success, hasn’t invested in expensive equipment or an editor; she believes content and captivating storytelling is more important than polish. “Your camera quality doesn’t matter,” she says.

Some of the videos she’s most proud of showcase documents written by science greats. “What I have found has worked well for me has been finding original copies from a Cambridge library online of Newton’s notes that he wrote in quarantine or finding an actual copy of Einstein’s thesis and reading through it,” she says. Others showcase Hendy’s quirky creative spark – who else would think to combine Babylonian maths with baking, recreating an ancient maths tablet in gingerbread?

Hendy advises that while not every scientist needs their own YouTube channel – it’s so hard to juggle research and social media that “it would be better for them to find creators that are working in the niche” – there can be unexpected benefits. “On grant applications, there is often a part where they ask you to say how you’re going to do science communication as part of the project,” she says. And scientists with an audience may have a better chance of succeeding, she adds.

Next steps

Hendy is now participating in a government program for YouTube creators, called Skip Ahead. “I applied for a grant and I’m producing a short film about mathematics that will be released on my YouTube channel in July.”

Her next goal is to partner with universities or scientific organisations, to help take their research to the general public. “A lot of what does well on YouTube is personality based,” she says, adding that institutions often struggle to get traction, “unless they have a personality step up and take control of it in a consistent voice”.

She’s also cultivating an audience on another social media platform. Despite initial skepticism about TikTok as a platform for science communication, Hendy decided she wanted to be a part of it. “I’ve seen how big TikTok has grown,” she says, describing the audiences as huge and “very dedicated”. Recently, she’s discovered there are some TikTok initiatives for educational content.

Hendy says moving to social media turned out to be the right decision, a successful realisation of her original motivation for studying science. “I was attracted to the idea of being a lecturer or a professor because I did want to communicate science,” she explains. “If I was still at my PhD, I might graduate and be a lecturer. At best, I might be able to reach a few hundred people a year.” This way, she says, “I reach millions of people every month.”

Article by Felicity Carter

Photo Supplied

Comments are closed.