Rare aesthetic. If that catchphrase means anything to you, you’re probably under 18, female and a TikTok native.

Or you might be Dr Karl: an over-18 (73, in fact) male and one of Australia’s most experienced and trusted science communicators. If TikTok gives him a new platform to share scientific truths with a young, female audience … pass him a silly hat and watch him bust some moves. He’s in – rare aesthetic and all.

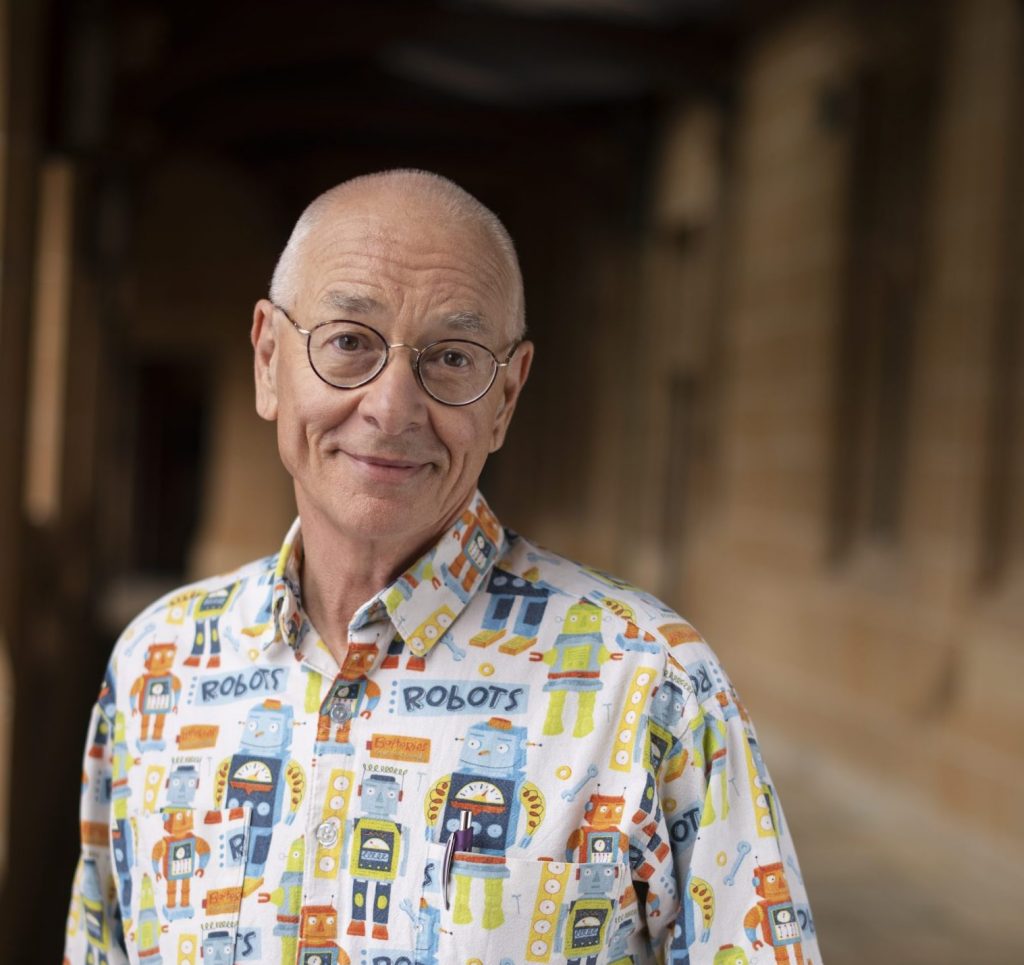

Dr Karl Kruszelnicki has always brought the wonder. A science-popularising pioneer with global clout, colourful shirts and a devoted audience, he’s received major accolades in recognition of his capacity to talk science to everyone, including the first (and only) Julius Sumner Miller Fellowship at the University of Sydney and an Ig Nobel Prize from Harvard University for his research into belly-button fluff. He won the 2019 UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science, the first Australian to do so. Previous winners include David Attenborough, Bertrand Russell and David Suzuki.

He’s authored nearly 50 books, created podcasts and television series, and has told countless stories on radio programs across the globe ever since he switched from being a doctor in a children’s hospital to a science communicator more than three decades ago. “I made the decision to go to where I could do more good, which was in the media,” he says.

The twin threat of climate change and a pandemic – both “a clear and present danger” he says – and the digital environment represent a significant challenge for science communicators. Misinformation is rife, straight facts are up for interpretation by the ill-informed, and trolls are taking aim at experts, Kruszelnicki included. Now more than ever, we need the wonder.

“It shows I’ve got more work to do,” he shrugs. “So, I’ll just keep doing the work.” As he tells his TikTok audience, “My joy is spreading the word that science is a way of not getting fooled.”

New platform; no fear

For Kruszelnicki, the basics of his effective, high-energy brand of science communication haven’t changed much since his first media appearances in the 1980s. “It’s an ancient formula,” he says. “Start with something amazing. Secondly, explain; because it makes people feel ‘smarterer’. And the third part is that you finish off with a joke.”

When errors crop up in the facts he shares (and they rarely do), he corrects them quickly.

But some things have changed. Now, keyboard-warrior armies that could be based anywhere in the world form attack squadrons to cast doubts on scientific evidence and spread conspiracies. There are new audiences and new platforms for communication that, just as they spread “alternate facts”, also provide exciting new channels for truth, says Kruszelnicki. Channels such as TikTok.

“In general, one-third of all TikTok users are under the age of 15 and two-thirds are female,” he says. “I see this is a duty, to help them get real information, rather than lies. You’re getting through to people before – you hope – they’ve got wrong things firmly implanted in their brain.”

TikTok offers an incredibly important audience, says Kruszelnicki, but you need to communicate to them on their terms. “I’ve got some advice from a six-year-old daughter of a neighbour of mine who said ‘Dance a lot and do experiments’,” he says. “I hired my daughter and two nieces, average age of 18, to do the production and I do the content. And so that way, I can get across to them.”

New decade, same problems

Underpinning every word Kruszelnicki puts in the public space on any medium is his astonishing breadth of his knowledge, research and recall. He has degrees in physics and maths, biomedical engineering, medicine and surgery, as well as a wealth of life experience. A typical working week involves an “infinite” amount of reading, he says, churning through a metre-high stack of journals and articles each month and $10,000 worth of scientific literature each year.

Kruszelnicki has always mixed it up – astronomy and belly-button fluff, intergenerational trauma and dog dreams – but the science of COVID-19 is currently a recurring theme with his audiences.

A related subject, immunisation and vaccine misinformation, propelled him into the showbiz of science in the first place. He recalls when a well-known current-affairs program “gave equal time to real scientists as to crackpots” in a story about a vaccine in the 1980s, it undermined confidence and reduced herd immunity. “In the children’s hospital, we started seeing dead babies, after a long period of very few dead babies from whooping cough,” he says.

Now, on social platforms that were unimaginable 30 years ago, he’s dancing in “Get vaxxed” videos and explaining why ivermectin, a treatment for animals with parasites, neither cures nor treats COVID-19.

“There’s a huge amount of misinformation around,” he concedes. “I did a TikTok on the stats about dying from the vaccine or dying from the virus and of the 4,000 or so comments, the vast majority are telling me that I’m completely wrong. Interestingly, I’m seeing the same pattern that I’ve seen with climate change and electromagnetic sensitivity, the semi-regretful: ‘Dr Karl, I really used to respect you. But now that you’ve done this, I’ve lost all respect for you.’ About 5% of all the comments are along that line,” says Kruszelnicki.

Tough skin

Kruszelnicki has been fighting for positive engagement with science for such a long time that you might think the attacks could leave him bitter and demoralised. But you’d be wrong.

“I don’t give it any of my emotional processor cycles at all,” he says. “These are people who have been organised into assault trees, where they’ve been told to ‘go and pick on this guy’. With ivermectin, for example, after I posted something on Twitter, we started getting huge numbers of people responding from the US. It’d be a pointless waste of my resources to give any emotion to at all. All it can do is make my life worse and make me less effective.”

Kruszelnicki may harden his heart, but he follows the metrics and analyses the engagement data, because it tells a story. A cute TikTok post he made about why a foetus hiccups in utero illustrates the complexity of science communications in the 21st century. With three million views, mostly from the US, his story was seized on by ‘pro-lifers’ as proof that abortion is wrong. Another, about the risks of the vaccine relative to the death rate of the virus, drew a big audience – but not, perhaps, the one he imagined.

“The overwhelming vast majority, 80 plus percent of people, were saying, ‘You’re crap, it’s all lies!’ They watched it only to debunk it, which to me is further reason to keep doing it” he says.

Kruszelnicki has always known that good communication needs to blend funny and serious. But developing a presence on platforms such as TikTok has reinforced the need for artistry and science to meet, out of respect for the medium and to entertain and inform its audience. For every tough COVID truth or vaccine fact, there needs to be silly dance, a poo joke or a tour of his shirt wardrobe, which is full of colourful creations made by his wife, Mary.

Kruszelnicki admires the work of other science communicators: right now, he’s a fan of Coronacast, Tegan Taylor and Norman Swan’s podcast, which is making sense of the pandemic. “They do an absolutely gorgeous job of making it understandable. And almost certainly, they will have saved many lives,” he says.

And, with lives at stake, does he feel a sense of urgency about communicating science in an age of mistrust?

“Well, yes, and no and yes again,” he reflects. “Part of the problem is that I have a scientific background. And because I have a scientific background, I know that science is not a bunch of facts. If you want a bunch of facts, go to an encyclopaedia.”

“But science is something different. It’s an active dynamic process for trying to understand the world around you. And then, accidentally, it leads you into a situation where you’re going to avoid getting fooled. For me, having been doing science ‘on and off’ all my life, it’s just so obvious that there are some things that are true and some things are not. But for those who have not been lucky enough to pick up a bit of science, they can get fooled.”

Article by MIchelle Fincke

Photo Credit: Ross Coffey