Marc Abrahams discusses the value of a laugh when it comes to communicating off-the-wall science.

Can sex improve nasal breathing? The answer, it turns out, is yes. Last year, researchers in Germany and the UK examined the nasal function of 18 heterosexual couples before and after intercourse; they concluded that sexual climax could improve nasal breathing to the same degree as a decongestant drug for up to an hour.

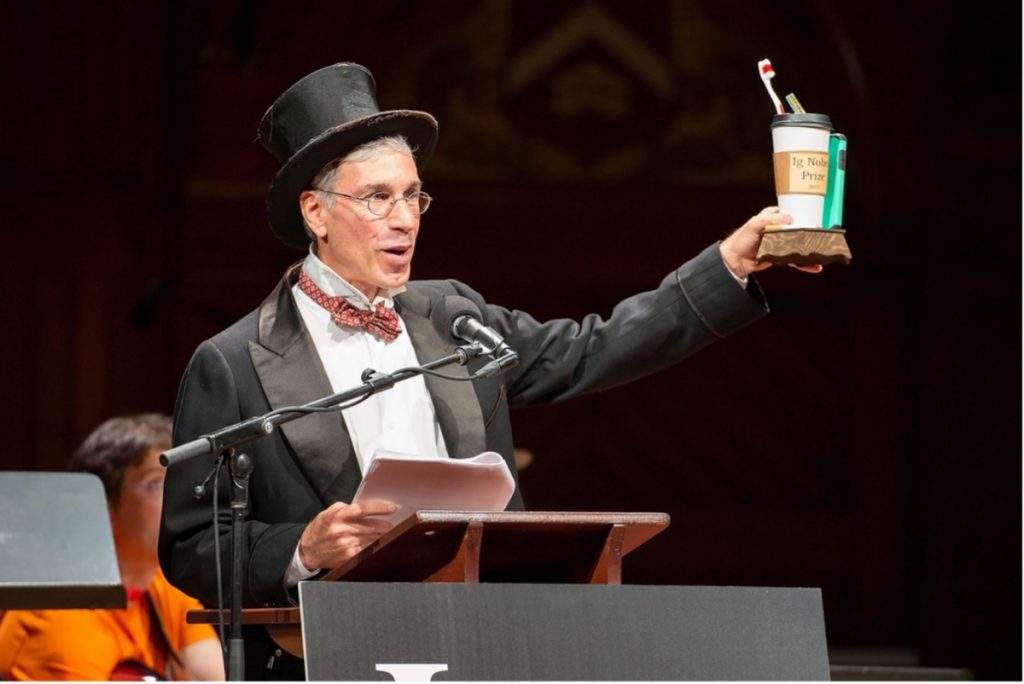

In recognition of their work, the scientists received the 2021 Ig Nobel Prize for medicine – one of ten satirical honours awarded each year to highlight achievements in scientific research that make people laugh, and then think. Established in 1991 by Marc Abrahams, editor and co-founder of the Annals of Improbable Research – a US-based magazine devoted to scientific humour – the Ig Nobels are a pun on the Nobel Prizes and the word “ignoble”, meaning “non-noble”.

Other Ig Nobel laureates include the designers of a so-called emergency bra, which can be readily transformed from undergarment to facemask, and the scientists who attempted to identify narcissists by the shape of their eyebrows. And let’s not forget the materials engineer from Iran who invented the automatic diaper changer and butt-washer machine (parents of young children can sign up to the waitlist here).

The idea of the prizes, says Abrahams, is to celebrate unusual and imaginative research projects, rather than make jokes at the researchers’ expense.

Picking a winner is a time-intensive process, which sees Abrahams plough through many thousands of research papers to look for the sweet spot in a Ven diagram where amusing and interesting collide.

“We work really hard to find them,” Abrahams told The Brilliant. “We also get about 10,000 nominations throughout the year from the general public. You learn quite quickly to recognise the papers that have no chance and quickly eliminate those so you can focus on the minority that are great.”

It remains an imprecise method, says Abrahams, and in the end, it’s a gut decision. “We like to pick things that are completely surprising to everyone. Their first reaction should be to laugh,” he says. “We also choose stuff that will grab people’s interest and make them think. If you’ve got both, then you’ve done a good job.”

A different kind of attention

This light-hearted approach to the awards has taken off – the journal Nature has hailed the Ig Nobels as “arguably the highlight of the scientific calendar” and Le Monde newspaper in France called Abrahams the “Pope of improbably science.”

The 2022 Ig Nobel ceremony is set to take place on September 15th as an online event, but Abrahams hopes that the proceedings will return to the pre-pandemic in-person gala at Harvard University in future years. He’s tight-lipped on which scientists are about to be bestowed the honour, but he says the winners have already been informed.

“We get in touch quietly and offer them the prize. If they want to say no, that’s fine, and we’ll never tell anyone that we tried to offer it,” says Abrahams. “That doesn’t happen very often these days, but in the early years it happened more frequently because not enough people had heard of the awards, and so they were suspicious of it.”

These days, more scientists know the awards are about spotlighting interesting research with a jovial spirit, rather than damaging reputations or making fun of anyone. Still, the occasional junior researcher declines to accept and Abrahams says that’s usually because they don’t feel supported by their supervisors, and they want to keep their heads down until they leave and find a job elsewhere. “When that happens, we get back in touch a few years later and reoffer it to them and invariably they accept,” he says.

One researcher, Sir Andre Geim, who works at the University of Manchester in the UK, went on to win the 2010 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on graphene after having claimed an Ig Nobel prize in 2000 for using magnets to levitate a frog. To date, he’s the only double laureate.

Winning an Ig Nobel gives researchers the opportunity to explain to a wider audience why their work is important. “They tell us that they feel it’s worth their time,” says Abrahams. “It’s a big world, with 8 billion people filling their days with something, and only a fraction pf those are scientists, but that’s still a lot of people. How many of them get attention outside of their immediate circle? If you win an Ig Nobel prize, a lot of people, including journalists, are going to want to talk to you and find out more about your work.”

As the awards enter their 32nd iteration, Abrahams hasn’t noticed any patterns emerging in terms of themes that go in and out of vogue in research. “It’s a collection of randomness,” he says. The challenge, he adds, is keeping things fresh. “My secret horror is that, if we don’t do a good job every year, there will come a time when people look at the winners and say, ‘This is like last year.’ I don’t want that to ever happen.”

Follow the Ig Nobel Prize on Twitter | Website

Story by Benjamin Plackett