Ella Marushchenko talks about the value of a good image in communicating the importance of science and research.

Striking the right balance between simplicity and detail is what Marushchenko strives to achieve every time she takes on a new project. For more than a decade, the North Carolina-based scientific illustrator has been distilling complex concepts into images that aim to make research more understandable and visually appealing.

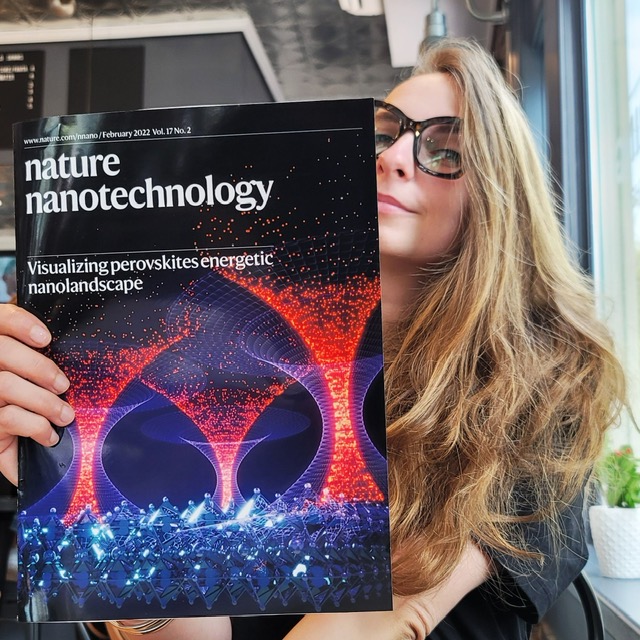

Marushchenko has accumulated an impressive roster of clients, including the Imperial College London, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Princeton University. Her work has been featured on the covers of high-impact journals such as Nature and Science. But it’s not what she set out to do with her career; in fact, she resisted science illustration at first.

“I grew up with artists, my grandma was an artist, and I went to university to study design and classical art in Russia,” she says. “I met a scientist called Sergiy Minko, [when I was just] out of grad school, who asked me to make some images for him and I declined because my background was in classical art and digital art didn’t really seem like my thing.”

But Minko, a materials chemist and nano scientist at the University of Georgia, persisted. He wanted Marushchenko to design an image of an innovative antifouling coating material, which he had created. “Scientists are so passionate about their jobs, and he explained everything to me, and we ended up talking for hours,” she says. “I said to myself that it was easier to agree.” The result ended up being the cover art for an issue of the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

“I was never specifically looking for this work, it found me,” she says. It wasn’t long, however, before she found the work to be rewarding.

The importance of a good image

The joy of science illustration, Marushchenko learned, comes from its capacity to communicate the importance of a piece of research or discovery in a uniquely concise way.

“Some people think science has nothing to with regular life, but that’s so not true. If we give it more attention and make it prettier and easier to understand, then that has value,” says Marushchenko. “It’s important to be this bridge between science and regular people.”

Most of her commissions come from individual scientists who contact her looking for images to supplement their research papers. Marushchenko first reads the study and then follows up with a phone call to make sure she has understood it. “They talk to me about the research and if they have any ideas or sketches for what they think the image could be,” she says. “Most often an idea will pop in my head when I talk to the scientist. It can dramatically change if I’ve missed something in their research, but that’s usually how it starts.”

For the most part, Marushchenko’s artistic process is digital. She draws rough shapes in computer software to get the outline and then adds detail and patterns. “It’s like sculpting, taking clay and making something from it,” she says. “Tumour cells, for example, are bumpy, so I’m cutting shapes and then adding texture.”

Once she has constructed an object, Marushchenko builds a virtual studio to house it. “It allows me to capture the objects from different angles with light coming from different places before landing on a final decision,” she says.

The process is slightly different for cover art. “If it’s a cover, then it’s supposed to be as attractive and easy to read as possible for people who aren’t experts,” says Marushchenko.

“You cut all unnecessary features to make it really attractive. My artistic background helps me here because I don’t feel any pain in the cutting because I believe simplicity is the right way,” she says. “It’s easier to understand and be attracted to something that’s nice and simple. If it’s too complicated, then people just turn off.”

Occasionally, scientists want to overload on the detail, which is something that Marushchenko pushes back on. “Scientists sometimes want to add everything to an image,” she explains. “It’s like cooking. You love onion and you love cinnamon, but you don’t put them together.”

All in all, it makes for quite the time-consuming process. “From reading the article, getting the idea, starting it and adding detail, it takes a couple of weeks to one month to complete a design,” she says.

A growing field of science communication

Science illustration is becoming a more mainstream form of art, says Marushchenko, partly because it’s a rewarding career path.

“Every artist wants their work to have meaning. Your work always has an impact on people’s lives when you do images for scientists,” she says. “It’s a great feeling to know you’re doing something important.”

It’s no surprise, then, that university programs are diversifying to train young artists with the skills to both understand the intricacies of science and translate that knowledge into something non-experts can readily understand. The ultimate goal, of course, is to increase society’s science literacy, which in the wake of a pandemic has never been more important.

“There’s a deep connection between the science and the audience,” says Marushchenko. “It’s an amazing feeling.”

Follow Ella Marushchenko on LinkedIn | Twitter | Instagram | Facebook | Website

Article by Benj Plackett

Comments are closed.